The Prehistory of Startups

It seems like the common thread that binds together these different cultures is a commitment to finding win-wins through the use of science and technology to build new products and services that give people a new way to communicate.

Where did startups come from?

In response to prompting from Tanner Greer, Patrick Collison laid out a list of books that represent an informal canon for Silicon Valley. Greer, in turn, explained how the canon represents a kind of ethos for Silicon Valley culture. What a culture values is what people living in that culture will seek to obtain, and the people who rule within that culture will tend to embody what is valued.

For those of us who love Silicon Valley culture, questions about how it originated or might be replicated are of perennial interest. To that end, a fact worth observing about Patrick Collison’s list is that only two of the books on the list[1] were published before the 1970s. Is Silicon Valley culture really of such recent vintage? The somewhat surprising answer seems to be yes. For another data point, at least according to some sources, the term “startup” as a description of a new company did not originate until the 1970s.

So where did startups come from? Why was it not until the 1970s that we needed a word to describe what is now so ubiquitous as to be taken for granted? For anybody interested in human progress, if not the history of human civilization itself, these are questions worth asking. Especially for somebody like me who has lived most of his life in Silicon Valley, the way things are done here is easy to take for granted. But in pondering these questions, and tracing back into history, I have gained an appreciation for just how contingent all of this might be.

For starters, Steve Blank has been publishing and presenting on the Secret History of Silicon Valley for at least 15 years now, and we are all in debt to him for his elucidation of the role that defense funding and purchasing of early communication, computing, surveillance, and reconnaissance technology played in the growth of Silicon Valley. Anybody interested in the history of Silicon Valley or the origin of startups should read, listen, or watch Steve Blank. I’m also very grateful to the Computer History Museum and its supporters for the work they’ve done gathering oral histories from some of the key people who participated in the early history. Let's have more of this, please!

Startup Culture

This humble essay is focused narrowly instead on what might be considered a true anachronism of Silicon Valley culture: AT&T.[2] The AT&T this essay is about is not the AT&T we know in the 2020s, but AT&T as it was built between the first Bell patent in 1876 and 1919 (when the hero of the story I have to tell dies). What I hope to describe here is how what we call “Silicon Valley culture” is really startup culture. There wasn’t a label for companies like AT&T in the late 19th century because there weren’t enough new companies building new products with new technology around back then. Nevertheless the basic character traits of the key leaders involved, the problems faced, and the manner in which those problems were solved will seem familiar to anybody working with startups in 2024. Or so I hope to show.

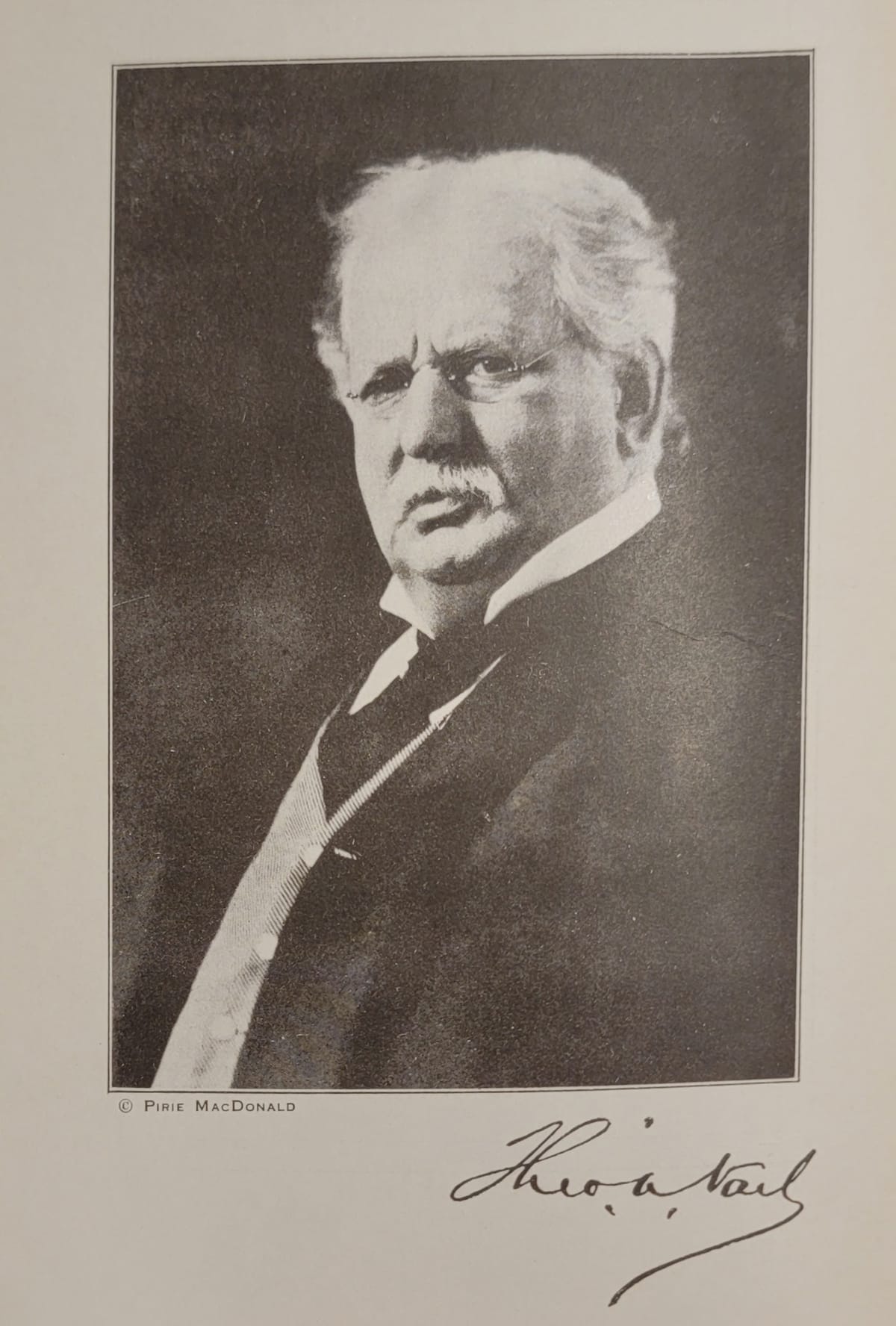

Specifically, this essay will focus on the personal traits and corporate culture developed by AT&T’s first General Manager, Theodore Newton Vail. In the future, I hope to expand to other leaders and corporate cultures widely separated from Silicon Valley in time and space,[3] but in this essay I will rely solely upon his singular example.

At the end of this essay, I offer a few conjectures. If startup culture was conserved across such a wide gap in time and space, then there must have been something else conserved that allowed for the same startup culture to take root and grow in Silicon Valley. I consider a tentative answer of network effects, which provide increasing gains with scale, and which are especially characteristic of new communication technology. We may see similar culture develop in industries defined by other economics, but startup culture may be more specific to the network effects that are most characteristic of new communication technology.

Last, but not least, Paul Graham published his essay Founder Mode while I was at work on this essay. The cultural impact of a specific type of leader cannot be discounted as an alternative explanation for what has been conserved as startup culture. In some sense, "Founder Mode" can be understood as a species of the "Great Man theory" of history. Given how this essay is devoted almost entirely to the description of a person who is far better characterized as a founder than as a professional manager, this essay can be read as supportive of Graham’s description of Founder Mode, and even as a useful data point in formalizing its definition.[4] There are many personality traits that Vail seems to share with contemporary founders. But what I personally find most compelling in the story is the specific mission and clear vision of how to accomplish that mission that Vail gave AT&T during his tenures. How long any culture can outlive its founder seems to be an open question, but if Vail’s precedent is any example, then the clarity of the vision and its communication, and the scope and potential impact of the mission, are at least as important as any character trait of the founder.

Theodore Newton Vail

Go West Young Man

Theodore Newton Vail was born in 1845 in Ohio and grew up on a farm outside Morristown, New Jersey. Vail’s childhood and adolescence showed him to be curious, social, self-motivated, and not strictly beholden to authority. He also showed what we might call today a high tolerance for risk, accepting jobs that would have been considered dangerous even by the standards of his day.

Vail was apparently a middling student overall, but always interested in science. Some of his extended family had played a role in the development of telegraphy. The school principal often asked Vail to remain after class to discuss what was new in the scientific world, including the polarization of light. But Vail often played hooky, including skipping school for an entire week at one time. His father at that time had said that he expected to have to support him.

Upon high school graduation, Vail worked for a couple of years as a drug store clerk before being sent to study medicine under his uncle. Vail never undertook that course of study, instead plucking a job as a telegraph operator in New York City from another uncle who worked for Western Union. While Vail worked standard hours from 8 a.m. to evening, from his diary we get the impression that he spent most of his free time eating oysters, playing billiards, and going to the theater. His carefree life ended less than two years later when his family moved from Morristown, New Jersey to Waterloo, Iowa, and he chose to join them there rather than remain without them in New York City. Vail spent two years in Iowa living the simple, but hardworking life of a midwestern farmer before again applying for and obtaining a job in 1875 as a telegraph operator, this time in Pinebluff, Wyoming.

To put how far out on the frontier this was in context, the Union Pacific railroad, which was the first to join the east and west coast of the United States, was not completed until the following year. A dead man lay on the train platform upon Vail’s arrival in Pinebluff. He had been killed by Indians the day before.

Pinebluff was a work and supply station, with work gangs paid to cut down and chop up dead but still standing trees for use as fuel for the train engines. The work gangs often got into scuffles with the Indians. One day when Vail arrived at work, the cords of timber piled up next to the station were on fire, and he had to scramble to put out the fire. On another occasion, after his brother had come to visit and the two were out on horseback, they encountered a group of Indians and were chased back to Pinebluff until some cavalrymen saw the race and came to their rescue. On election day, when a train full of immigrants passed through, he watched the men “invited from the coaches, duly marched to the polls, and the proper ballots placed in their hands.” Vail believed that they had probably been voted the same way at every station they passed that day.

Vail stayed in Pinebluff until another letter to the same rich uncle who had gotten him the job in New York City resulted in his appointment to a job as a postal worker on the Union Pacific railroad.

Going Postal

At 24 years old in 1869 Vail was both engaged to be married and a postal worker, responsible for riding the trains from Omaha, Nebraska to Wasatch, Utah and back, sorting mail received at each station along the way. Riding trains all day might sound relaxing to some in 2024, but bear in mind that it was not for some months after he began his route that the east and west coast legs of the Union Pacific were joined by the Golden Spike on May 10, 1869. While his uncle had done him a favor getting him the job, this wasn’t a job that was in high demand among government workers. Here’s Vail’s biographer:

It was a new venture; it ran through a wilderness and was of hurried, hit-or-miss construction. Its equipment was on a par with its track, and its mail clerks on a par with its equipment. It was said that anything human or mechanical not wanted elsewhere was turned over to that road. It was a good place for trying out new men.

Paine at 42.

While on the job, Vail survived a few derailments and one major wreck, which caused him a knee injury. He also learned how the system worked from the inside and on the front lines, developing a visceral understanding of the value of delivery speed. Eventually, he figured out how by sorting, bundling up, and labeling mail for the small settlements that could be reached only from particular stages, it was possible to get the mail to arrive up to a week earlier. He bought himself maps and marked out connecting routes, then memorized the names of towns of each to aid in sorting. Later he wrote these out on a card that he tacked up on the mail car so that both he and his coworkers could sort and bundle the mail for quicker delivery.

Over the course of several years, his intelligence, initiative, and hard work at improving the system earned him promotions that landed him in Washington, D.C., where he became part of a wave of reform to the postal system:

In that day the vast majority of federal employees in every Department were men incapable of making a living through ordinary means, dumped upon the government by unscrupulous politicians. From the earliest day of the mail service its growth had been impeded and retarded by time-serving officeholders, their practices often aided and abetted by those occupying places of the highest trust.

Paine at 69. At 31 years old in 1876, Vail was appointed General Superintendent of the entire United States Postal Service when his boss retired. He worked long hours throughout these years, and was acclaimed for the improvements to the service he pioneered.

Perhaps the most dramatic scene from this stage of Vail’s career occurs after he has become General Superintendent, and is negotiating to secure service for an overnight route from New York to Chicago, thereby allowing next day delivery of mail between those cities. This negotiation took place, on the one hand, between members of Congress who had to pass bills to fund the service, and were refusing to do so for more than low limited rates, and, on the other hand, the railroad barons, including Cornelius Vanderbilt, who retained the residual profits from whatever railroad service was provided. The new routes were not particularly profitable for Vanderbilt, who when he heard that Congress had limited the rates to $600 per mile, had taken his trains off the new route.

Vail met with Vanderbilt in person in July 1876, after having reached a tentative agreement with Vanderbilt’s chief rival at the time, the Pennsylvania Railroad. Vail’s biographer recounts the scene:

“Mr Vail, I understand you have made a contract with the Pennsylvania for the Western mail.”

“No, Mr. Vanderbilt, I have only agreed to give it to them until you provide an equally quick service.”

“Very well,” said Vanderbilt, “then I will put all through mails off the road altogether.”

Vail reflected a moment, then quietly:

“If you do that,” Mr Vanderbilt, “we shall be obliged to reduce the pay for the local mails to a nominal amount per mile.”

Vanderbilt was much irritated.

“In that case,” he said, “I'll throw off every sack of mail from our trains.”

“And in that case, Mr Vanderbilt, it will become a fight between you and the people living along the road, who will have no other way to get their mails.”

Paine at 84-85. Paine notes that “the interview did not end pleasantly.” But halfway back to Washington, Vail got a telegram asking him to return. Vanderbilt had given his secretary authority to adjust matters, with the end result being that service to the new route was restored.

In this middleman role, Vail ended up facilitating a certain amount of questionable back scratching between Congress and the railroads. When a Senator proposed supporting a bill to raise the rate limits in exchange for a 10% commission, Vail’s response was: “Well, Senator, it is between you and the roads. All I can do is report to them what you propose.” The proposal was accepted by the railroad owners. Vail commented to his biographer: “That was the only time that I was ever a party to anything that resembled graft.”

General Manager and First Retirement from AT&T (1878-1885)

Vail’s Appointment

Vail was hired as the first General Manager for AT&T in 1878, two years after a patent had been granted to Alexander Graham Bell in 1876. The telephone had gotten some good publicity through a demo at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876,[5] but neither Bell himself nor anybody he had associated with seemed to have a business plan that anybody wanted to finance:

[Bell's] discovery was not in any sense an improvement — a new and better way of doing something that had been done before — it was doing an entirely new thing; in effect, it was adding a sixth sense to the human equipment; it was bringing within hearing distance every human being in the world. To make it a commercial investment was another story. One might suppose that after the publicity given it by the Centennial success, the matter of financing would be easy enough. Nothing could be farther from the facts. To the business world the telephone was just a toy, an interesting and wonderful toy, but of no real practical use, certainly not a thing in which to invest capital...

Paine at 98 (italics in original). By the end of 1877, Bell and a few colleagues had cobbled together enough seed capital to get almost 1,000 telephones in use around Boston, but they were far from profitable. And in early 1878, the telegraph company Western Union — the same that had a year earlier refused to buy Bell’s patent for $100,000 (or about $2.5 million in 2024 dollars) — sued for patent infringement, and entered into direct competition by selling its own telephones. Bell was burning cash with no foreseeable prospects for profitability.

Into this mess Vail waded in the spring of 1878. One of Bell’s angel investors, Gardiner Hubbard, a lawyer and lobbyist for nationalization of the telegraph system, had met Vail and demonstrated the telephone to Vail while serving on a Congressional Postal Committee. Hubbard was impressed with Vail and Vail with Hubbard:

Vail’s former interest in patents that would revolutionize the world dwindled into insignificance as he contemplated the possibilities of this one. Hubbard's wildest dreams could not equal his own. ... [Vail] pledged himself to take all of the stock that he could raise money to pay for.

Paine at 107. By early 1878 Vail had accomplished what he had hoped to accomplish within the Postal Service, and was wrangling with Congress over whether or not his personal expenses would get paid. When Hubbard heard that Vail was interested in looking for another job, he told him to look no further. The Board was apparently concerned about Vail taking the title of Superintendent from Watson, who had been working with Bell from the beginning. But Watson turned out not to care:

As for Vail, he said he didn't care what he was called so long as he had a job where there was a chance to do something and where his work would count. The delegation assured him that it would be that kind of a job, and it was agreed that his title was to be “General Manager” of the company.

Paine at 112. He was 33 years old.

First Things First

Vail’s first acts as General Manager included reincorporating the company[6] in New York and traveling to Menlo Park, New Jersey to meet with Thomas Edison — a hostile witness in an ongoing litigation. Vail’s approach to Edison must have been somewhat disarming, because Edison apparently admitted to Vail that Bell was the inventor of the “magneto telephone.” Paine at 116. The litigation between Western Union and what became AT&T was not settled until November 1879, but having satisfied himself in June 1878 that Bell was the first and true inventor, Vail proceeded to convince everybody around him of that by acting confidently and decisively on his conviction from that point forward:

About the first thing he did was to send a copy of Bell's patents to Bell agents in different parts of the country, calling upon them to stand by their guns: “We have the only original Telegraph patents [ he wrote], we have organized and introduced the business and we do not propose to have it taken from us by any corporation.”

Paine at 125. The conviction Vail showed here was significant. The ultimate question of whether Bell should be entitled to the telephone patent in view of conflicting claims by other inventors (who were backed by Western Union) was a close question. The full story involves accusations of suborned perjury of a Patent Examiner and bribery of the U.S. Attorney General by a Bell competitor, and there are some who still believe that Bell stole the invention from Elisha Gray in a conspiracy with his lawyers. In the end, however, it was decided by the Supreme Court in 1888 that Bell was the first and true inventor, as Edison had at least partially admitted to Vail in private in 1878.[7]

That Bell’s patent would ultimately be held valid and enforceable was an important judgment by Vail, but perhaps even more important was the experience he had in building the postal service. Vail’s biographer quotes one of Vail’s contemporaries on this point:

An important fact that few people appreciate, either within or outside the Bell system, is that what was required from Dr Bell was nothing more than the right to use his idea. There was no commercially practical apparatus, there was no science or art of telephony. The undertaking of the Bell System when Mr. Vail became its manager was to develop this art and science and to build upon it a great public service. The undertaking was not as people are apt to believe, merely to take a commercially practical piece of patented apparatus and put that on the market. Everything had to be created.

Paine at 160 (quoting a conversation with N.T. Guernsey). Bell had the original idea, but he needed Vail to help take the idea from 0 to 1.

The Vision of Universal Service

More importantly, Vail brought his deep understanding of incentives and the need to find mutually beneficial deals to bear on expanding the network:

Contracts made with local companies, in towns of whatever size, were similar to that made by the New York company — the Bell company taking stock for its privileges, thus becoming a partner in the business, driving also an income from the rental of the telephones.

Paine at 127. Vail turned local companies into sales agents, leveraging their superior relationships with potential customers through profit-sharing. But even the costs of making the telephone sets — not to speak of the costs of stringing or digging cables — were significant enough to require massive capital expenditures that needed to be financed:

Manager Vail was not dismayed by the prospect. He worked always as if he had infinite resources of capital as well as courage, and had a permanent company behind him. He laid out his campaign on a large scale and constantly introduced new features - among them a 5-year standard contract which required the local companies to build exchanges and confined them to certain areas.

Id. Sound familiar to any entrepreneurs you know today? Where did he find the courage?

In his vision he saw interlinking wires extending from city to city and across states. He even began securing interstate rights, in a day when there was no wish to deny a privilege the value of which was considered negligible. The plan in his mind was to create a national telephone system in which the Bell company would be a permanent partner. Perhaps he did not then put into words his later slogan, “One policy, one system, and universal service,” but undoubtedly the thought was in his mind.

Paine at 128. This was the mission and vision that sustained the operation of what became AT&T from its inception all the way through until antitrust law broke it up in the 1980s, almost exactly 100 years later.

Growing Pains

Bear in mind that in 1878 a telephone call “often suggested a Fourth of July celebration rather than an interchange of human speech,” and was “more calculated to develop the American voice and lungs” than to promote conversation. Paine at 129. For at least a few months in 1878, it looked as if the company was ruined after Edison came out with an improved transmitter, and customers began clamoring for telephones that worked as well as Edison’s. Western Union was a juggernaut, with an already established network of wires, offices, and agents, not to mention superior access to the media. In Philadelphia, the company’s local partner was forbidden from putting up wires and its linemen were more than once arrested. And the company was still burning through cash.

In the midst of this, Vail was offered positions with higher salaries at more established companies. Id. at 130. Bell was in England trying to interest foreign investors to no avail. His biographer reports:

Theodore Vail’s calmness during these trying days was a large asset. [The company staff], dismayed at the financial situation, and at the powers in Array against them, would look over at him sitting at his desk, serene, undisturbed, quietly writing, and take courage.

Paine at 131-2. Much later he was asked of this time:

“Didn’t you ever get discouraged?”

“If I did,” Vail answered, “I never let anybody know it.”

Paine at 133. A hint that Vail had been in “the struggle” that Ben Horwitz described in The Hard Thing About Hard Things?

The Tide Turns

The tide turned in Bell Telephone’s competition with Western Union when Francis Blake Jr. invented an improved transmitter, which he sold to Bell Telephone in exchange for stock. Blake’s choice to sell to a startup rather than an incumbent is an interesting anachronism in itself, and we don’t seem to have much of a record as to how he made that choice. It was the beginning of the end for Western Union. Between the improved transmitter winning customers to Bell Telephone everywhere and an accusation of patent infringement filed in Massachusetts, Western Union was now on the defensive, and Vail pressed his advantage by sending out circulars to customers “respectfully advising” that Western Union did not have a patent license for its telephones, and that anybody using anything but a Bell telephone might be compelled to pay twice.

In response, Western Union offered to leave the local telephone business to Bell in exchange for control of inter-exchange and toll lines (or what would later be called “long distance”). Paine at 137. While some at Bell Telephone were in favor, Vail opposed. How could the vision of universal service be achieved in that way? The competition and lawsuits continued until a settlement was reached in November 1879, when Western Union conceded that Bell was the inventor of the telephone, and retired from the telephone business in exchange for a license to use telephones on their own private wires and a promise from Bell Telephone to keep out of telegraphy. As part of the settlement, Bell also took over the existing Western Union telephone network, which included 56,000 telephones in 55 cities.

Blitzscaling

With Western Union out of the way, the sole focus was on borrowing and building. The capital expenditures required for stringing (and later burying) wire and manufacturing telephones were enormous, and even though customers were willing to pay handsomely for the privilege of using telephones, it took time for the company to recoup enough in revenue to realize any profit. Then, as now, cash flow was king. While Bell Telephone was not profitable on paper, investors could see the cash coming in from subscriptions, began to buy into the growth story, and stock in the company, which started at $50 a share, was selling for $1,000 a share after the settlement with Western Union was announced.

Just before the settlement, the investors at Bell Telephone decided it would make more sense for the New York local telephone company to merge into its parent. There was some overlap in the investors, with Vail personally owning shares in both companies. Again this feels like an anachronism for the kinds of deals we have seen done by startup founders over 150 years later. In this case, Vail was able to convince the New York local telephone company’s shareholders to accept the offer from the parent company despite a competing offer from Western Union. The currency of Bell Telephone stock was simply more valuable than any amount of cash.

The basic pattern of buying out local networks and merging them into the parent was thereby established, and would be repeated over and over throughout the next decade and beyond, with Vail and the rest of the company relentlessly pursuing the vision of one system and universal service. At 35 years old Theodore Vail was a multi-millionaire (in 2024 dollars, $100s millions). He continued in his role as General Superintendent for another 5 years after the settlement with Western Union, at which point the pattern for growth had been established, he was exhausted, and had seen his wealth grow to what in 2024 would be billions.

But what caused Vail to pull the trigger on his first retirement? He told his biographer that:

[A] growing dissatisfaction with his position at this period was due in part to the company's reluctance to spend money and keeping the service at maximum, preferring to distribute larger dividends.

Paine at 173. The priority had shifted from growth to profit.

The Interregnum and Argentina

What did he do after his first retirement? Bought up a huge farm in Vermont, established a local vocational school, and continued the angel investing he had been doing since he was in the postal service.

Leveraged Investing

Vail loved leverage. According to a friend who knew him when still in the postal service:

His habit of lavish expenditure - though it was more than a habit it seems, it was a natural trait — I never could understand — he seemed to act on the certainty that the money would be forthcoming in due time. And it always was.

Paine at 69. His biographer notes that while serving as Superintendent of the Postal Service, he kept one of his clerks busy negotiating his personal loans at what were then the prevailing rates from 12% to 18%. (!) The principal he borrowed while Superintendent of the Postal Service was typically small, $50 or $100 ($1250 to $2500 in 2024 dollars). But “he had a natural gift for credits.” Paine at 70.

How was he spending this borrowed money? Mostly on investments:

He invested these modest sums in a few shares of some patent right that promised to revolutionize one of the world's important industries. These mechanical curios always fascinated him, and he collected stock in them as another might collect postage stamps or old prints. Once he joined with two associates in a company to perfect and promote a self-binding attachment for a harvesting machine.

Paine at 69. While living on the farm in Iowa, he had himself proposed a similar invention. On a trip to Washington, D.C. after his first retirement from AT&T, a former postal service colleague asked him:

“Vail, are you still borrowing fifty or a hundred dollars to put into some patent?”

“Well,” he answered, “I am still borrowing, just the same; only now it’s fifty or a hundred thousand.”

Paine at 150. The degree to which Vail felt comfortable borrowing and investing other peoples’ money might seem puzzling given his relatively humble upbringing on a farm. One potential explanation is that many farmers rely upon loans to finance their operations until harvest.

There is no way to know this to be true of Vail, much less of startup culture more generally. But it’s provocative given how many Silicon Valley founders are from the midwest, including Robert Noyce (Fairchild, Intel), Bill Joy and Scott McNealy (Sun), Larry Ellison (Oracle), Larry Page (Google), and more. Other founders, like Jeff Bezos, have explicitly tied their entrepreneurial mindset to experiences growing up on a farm. A separate history will have to be written about the influence of midwestern culture on Silicon Valley.

Angel Investing

What was Vail investing in after his first retirement from AT&T? Naturally, there were many foreign and domestic telephone companies. But he also invested in batteries, ash and garbage vaults, enameled leather, gunsights, and a Colorado silver mine. Paine at 151. Was there any theme to his angel investing? His biographer describes it this way:

That he hoped to make money on these many Investments is true enough, but the thought of profit was always secondary. His first idea was to establish, or extend, some important enterprise — some manufacturing or mining industry that would grow and grow and give labor and benefit to the race. He was pre-eminently a builder, a developer. Mere money — through the purchase of stocks in the market, for instance — did not interest him.

Paine at 151. There are some interesting parallels between this description of Vail’s approach to investing and modern investing frameworks, such as Environmental and Social Governance (ESG). So what was his track record? Not better than most entrepreneurs’ track records with angel investing:

None of these Ventures came to anything, but they all promised well and one after another kept him hopeful. Even their final collapse never discouraged him.

Paine at 69. An investment in an ostrich farm produced a single ostrich egg as a dividend for its investors before being written off. Vail wasn’t present to enjoy the omelet made from the egg with his co-investors, who were kind enough to send him the shell instead. Paine at 190. Then came the central heating system (the “Accumulator”) — a plan to supply superheated water from a central plant, like gas or electricity. His leveraged investments in bringing his vision of the Accumulator to customers nearly ruined him. Upon hearing the news of its demise from his butler, Vail responded:

“Well, Johnson, the Accumulator is busted. Where is the next crash coming from? Bring a bottle of champagne.”

Paine at 195. In fact, almost none of Vail’s passive investments seemed to do very well. Rather, it was the investments he made in which he was also active in operating.

Hydroelectric Power in Argentina

In the summer of 1894, one of the guests to his home in Vermont was an American astronomer who was in charge of the weather bureau in Córdoba, Argentina. Argentina at the time was one of the most successful economies in South America, and the astronomer described to Vail the unique opportunity presented in Córdoba to harness water power to generate electricity. Vail had since childhood been fascinated by South America, and agreed to travel down to Buenos Aires and Córdoba to assess the opportunity.

He ended up spending a decade traveling back and forth between the United States, Argentina, and London where he helped sell bonds to finance the development of the power plant in Córdoba to power electric railways to and from Buenos Aires. His personal involvement in these ventures seemed to make a difference in their outcomes, although undoubtedly that was partly because of the prestige he brought from his earlier tenure at AT&T and the U.S. Postal Service. The end result seems to have been a success for both the investors and the people of Argentina. At least until nationalization of their economy, which is another story. Things seem to be turning around in Argentina lately.

President and Second Retirement from AT&T (1907-1919)

During his interregnum in Argentina, AT&T began to suffer from the kinds of problems that Vail had foreseen would result from underinvestment in capital expenditures on their service. Cooperative local telephone exchanges sprung up around the country in an attempt to avoid paying AT&T subscriptions, which were seen as exorbitant:

Every telephone user — of the independents — was a stockholder who had joined in saving the world from the iniquities of the Bell. Many of the lines were “farmers’ lines,” single iron wires strung on rickety poles or nailed to trees, with as many as a dozen or twenty telephones on a circuit.

Paine at 224. But there was no connection between these local cooperative services and Bell subscribers, and there was no such thing as an antitrust authority to insist on interoperability. Talking to a Bell subscriber meant traveling to their home or office. In some cases, people ended up paying for and installing more than one telephone in order to have access to more than one network. Eventually it was recognized that the original vision of one system and universal service was the best policy, and AT&T continued to roll-up the local telephone companies, including the cooperatives.

Subscribers didn’t necessarily go willingly, and negotiations between the managers of the cooperatives and AT&T could be intense. Vail’s biographer tells a story of one local co-op manager arranging to meet with an AT&T executive at midnight in a hotel, where the manager arrived with his collar turned up, wearing a false beard. He was the president of the co-op, and had come to negotiate, but was mortally afraid of letting his shareholders and subscribers know that he was talking to AT&T. Paine at 226.

The Board at AT&T knew they needed a leader who understood and could communicate the benefits of the vision of one system and universal service in the way that Vail had. After twelve years of working with professional managers, including distinguished patent lawyer Frederick P. Fish — the same who founded leading patent boutique Fish & Richardson, which is still operating in 2024 — the Board turned back to Vail for help. He agreed and returned as President in 1907.

One of Vail’s first moves upon return was to consolidate. Twelve thousand employees were let go from the Western Electric plant. The engineering department of 500 employees, which had been spread across dozens of locations and subsidiaries, was consolidated into three labs in Chicago, Boston, and New York.

Next he chartered a yacht, and invited in small groups the prominent officials from each major subsidiary to cruise with him up and down the Hudson and along Long Island Sound, listening to their problems and entertaining them in regal fashion.

When it came time to prepare the financial statements for his first year as President, he was asked to consider omitting certain items from the company’s accounts. He refused, instead presenting financial statements that gave an accurate, if not flattering portrait of where AT&T stood at the end of 1907. Vail’s reports:

[W]ere never dry reading — something to be waded through for the statistical contents. They always contained a “story” which stockholders followed from cover to over.

Paine at 237. Before the report had been issued, at least some on the Board had complained about it being too candid. Paine at 236. But the shareholders loved it, with one from friend London saying the report of 1907 “never was equaled and never will be surpassed.”

The report provided a plain blend of factual statements about the business along with narrative explanations of the accounting principles, economics, and even technology behind the telephone system — a style that might be familiar, for example, to readers of Warren Buffett’s letters to his shareholders. In it, Vail took up again his mission of educating his shareholders, customers, and the public at large on the win-win deal represented by “one policy, one system, and universal service.”

The same simple, direct, and persuasive style of communication came to the aid of AT&T after government regulators got involved:

[W]hen special committees began the investigation of large public telephone utilities ... President Vail appeared with great willingness and testified without any constraints or concealments. At such times he would say: “What is it you would like to know? We will show you anything you want to see, and do anything you ask. Just tell us what you want."

Paine at 238. The trust he engendered in everybody who had anything to do with the telephone system allowed it to resume its growth into a single, unified network that covered the entire United States.[8] “Take the public into your confidence and you win the confidence of the public” was how Vail described the strategy. Paine at 238.

This mutual trust culminated in Vail’s complete cooperation with the United States federal government when control of the telephone network was taken during World War I. Vail cooperated fully with the Postmaster General who took control of the network in 1918 for a period of a little less than one year, providing reassurance and encouragement to cooperate for the telephone network employees. The letters exchanged between the Postmaster General and Vail upon return of the network in 1919 are about as close to love letters as you’ll find in official correspondence between government officials and corporate executives. Vail saw the need for cooperation by AT&T as part of the war efforts, and got behind the government despite whatever misgivings he may have had about Washington politics after his experiences in the Postal Service before AT&T.

Serious Hobbies

One more vignette from Vail’s life story is worth recalling because of how it prefigures startup culture. In the fall of 1912 he gave a speech to a small group of people gathered as a Hobby Club at his home in Vermont. In his speech he observed:

Many have the same idea of a hobby that a political leader had the other night when he spoke of an aggressive, bumptious, persistent candidate with whom he was not in sympathy. “Look at him,” he said, “like a child in the center of a room ferociously rocking his hobby [horse] and thinking he is getting somewhere. He isn’t. He is only wearing a hole in the carpet.” ...

A man’s hobby is, however, not to be dealt with except seriously. Any serious, concentrated pursuit is a hobby. The very essential of a hobby is earnestness, and that is why hobbies have done so much in the development of the world, more than they sometimes get credit for, since by many persons hobbies are not regarded as implying anything like application, concentration, broad and exact information, without which any hobby is a failure.”

Paine at 255. It is impossible not to see the similarity in the observations and even phrasing here to one of Paul Graham’s most famous essays (“How to Do Great Work”) (“If you're earnest you'll probably get a warmer welcome than you might expect. Most people who are very good at something are happy to talk about it with anyone who's genuinely interested. If they're really good at their work, then they probably have a hobbyist's interest in it, and hobbyists always want to talk about their hobbies.")

Vail went on to talk about his own hobby: “Intercommunication.” Vail lived only until 1919, much too soon to see the internet that the hobbyists at Bell labs he helped establish (and inspire) would help build only a few decades later. But even in 1912, he understood that “was and is the advance agent of civilization, of all intellectual, commercial, and social development.” Paine at 256. As Vail saw it:

The development of intercommunication and the development of the world, the growth and evolution of man, of civilization, of the economic world as we know it, have gone hand in hand, or rather step by step, along the trail made by intercommunication.

Paine at 256. Vail would not live to see how far AT&T would develop intercommunication, but there can be no doubt about his influence on AT&T culture.

Content is Not King

I finish the biographical portrait of Vail with his speech about hobbies and intercommunication for a reason. In learning about Vail, I was startled by how many parallels there are between his personality and experiences as an entrepreneur and angel investor and those of contemporary entrepreneurs and angel investors. It is tempting, therefore, to conclude that if Silicon Valley culture is an example of some more universal startup culture, then both are ultimately rooted in the personalities of strong leaders like Vail. I have to admit that in writing this essay, I have been persuaded more to that view than I have by anything since I completed Caro’s biographies of Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Which is why I feel it’s important to consider an alternative or perhaps complementary theory about what is conserved among early AT&T culture and the culture of Silicon Valley startups like Fairchild Semiconductor, Google, HP, Intel, and Oracle, and startups that originated elsewhere like Amazon and Microsoft.

In March 2000, the dot com bubble had peaked and the stock market was already down 50% from its peak. Many startups had imploded already, and there were many more that would implode before the market could recover. Many in Silicon Valley were questioning whether the vision of the internet transforming the world was an illusion.

Andrew Odlyzko, a mathematician from the University of Minnesota, published an article titled “Content is Not King” in January 2001. In the article, he argues:

[C]ommunications is huge, and represents the collective decisions of millions of people about what they want. It is also growing relative to the rest of the economy in a process that goes back centuries. As a fraction of the U.S. economy, it has grown more than 15-fold over the last 150 years. The key point[:] most of this spending is on connectivity, the standard point-to-point communications, and not for broadcast media that distribute “content.”

Odlyzko goes into detailed analysis of the revenue and expenses of building communications networks and producing content in different industries, both as they existed when the essay was published in 2001 and historically. The last section before his conclusion is titled “Value of social interactions,” and in it he summarizes what he views as important historical lessons:

One is that the growing storage and communication capacities will be used, often in unexpected ways.... Another important lesson is that the value of the myriad social interactions has often been underestimated.

The first telegram read “What hath God wrought?” The first phone call was “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” People weren’t using the internet to consume great works of literature. They were using it to share photos of cats. At least from Odlyko’s point of view, what was driving the development of technology in the 20th century was the gravitational pull of social interaction. From where I sit in 2024, he seems to have been right about this. Search (Google), social media (Facebook), and even crypto (Coinbase) seem each to manifest a new mode for human communication.

At the same time, in his conclusion Odlyzko notes that most telephone revenues come from businesses. That seems to have reversed since the telephones became smartphones and the connections became wireless. But business spending on internet connections still seems far greater than consumer spending in 2024. Odlyzko concludes:

Content has never been king, it is not king now, and is unlikely to ever be king. The Internet has done quite well without content, and can continue to flourish without it. Content will have a place on the Internet, possibly a substantial place. However, its place will likely be subordinate to that of business and personal communication.

Conclusions

Odlyzko’s conclusion is made specifically about the relative value of new content compared to that of new forms of communication, a question that was top of mind for the media and entertainment industry in 2001. Yet the conclusion might be understood more generally as an observation about the relative value of new forms of communication versus the value of other new kinds of goods and services.[9] The economic characteristics of new forms of communication are unique in how they increase with scale — so-called “network effects.”

Looking back at Vail, it is interesting to observe how his operating roles — at the Postal Service, at AT&T, and maybe even in building hydroelectric power and railways in Argentina — were all in industries that had network effects because of how they facilitated more social interaction. In some sense, Vail was the product of his unique environment, in which the companies he led sought to enhance human life, and specifically social interactions, through improvements in technology. Was AT&T culture more the product of Vail’s personal vision and mission, or rather an inevitable consequence of the gravitational force of human social interaction that was made manifest in the advance of communication technology?

As an adopted identical twin, I have a unique appreciation for how genes and environment interact in ways that produce surprisingly rich variations in experience. In contemplating the question of startup culture, I am personally inclined to the view that what is conserved across time and space in startup culture are the leaders and their followers who share a vision and common mission of somehow making life better for their fellow humans. There are plenty of new companies that are founded to make money. People are seldom more innocently employed than while making money. But these kinds of companies have been around forever, and there was no need to coin a new word (“startup”) to describe such companies.[10] It seems like the common thread that binds together these different cultures is a commitment to finding win-wins through the use of science and technology to build new products and services that give people a new way to communicate.[11]

Bibliography

Quotes are from Theodore N. Vail, A Biography by Albert Bigelow Paine (Harper & Brothers 1921). It’s worth noting that the text of this work entered the public domain in 1997, only a year before the Sunny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act would have extended its term for another 19 years until 2016. In any case, it is now in the public domain. (And the photographs of the work shown are photographs that I took, copyright to which I hereby dedicate to the public under the Creative Commons Zero license.)

Readers interested in reading more about the history of AT&T and Bell Labs should also check out Brian Potter’s essays at Construction Physics, including:

Building the Bell System (which inspired my digging into Vail’s biography)

What Would It Take to Recreate Bell Labs?

And his Bell Labs Reading List

Asimov’s Foundation and Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. ↩︎

Special thanks to Brian Potter for his recent publication about AT&T, in which Theodore Vail featured. ↩︎

Benjamin Franklin and the network of printers he helped establish through apprenticeship and partnership provide another provocative historical anachronism for startup culture. Similarly, the story of George J. Mecherle and the founding of State Farm Insurance has many interesting parallels. To be left for another day. ↩︎

Jessica Livingston’s Founders at Work has 32 data points but was published in 2007. ↩︎

As the story is told, the telephone hadn’t garnered much attention until the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro II (“the Magnanimous”), who was also a judge at the Centennial Exposition, listened and exclaimed, “My God, it talks!” Paine at 96-7. ↩︎

The first corporation to form was the Bell Telephone Company, which ultimately merged into its subsidiary American Telephone & Telegraph on December 30, 1899. The merger was apparently necessitated by Massachusetts corporate laws that limited market capitalizations to ten million dollars. (What was Massachusetts thinking?) ↩︎

Vail’s biographer also spends an entire chapter describing the many other inventors who claimed to have invented the telephone or improvements to the telephone that Vail dealt with during his early tenure as General Superintendent. Vail was open minded to claims of improvement, including to the claimed invention of a wireless telephone, but was also firm in requiring demonstrations that in nearly all cases were impossible. There were also hundreds of lawsuits, including several funded by a group that included a General and two southern Senators who sued for annulment of the Bell patents. The latter continued until 1896, three years after the original Bell patent had expired. Paine at 154-8. ↩︎

Employees too seemed to trust Vail’s leadership. During his tenure he instituted a number of employee benefits, including sick leave and pensions for long-term employees. See Paine at 247-50. ↩︎

In the article, Odlyzko supports his argument with an argument based on Metcalfe’s Law and citations to another paper in which he analyzes whether Metcalfe’s Law holds for the internet. It’s also worth noting that Odlyzko began his career at Bell Labs, so there is at least some possibility that his conclusions in some way echo Vail’s own views on his hobby of intercommunication. ↩︎

If this conjecture is accurate, then “Founder Mode” may not be either a necessary or sufficient condition for startup culture. Rather, it may be a coincidental psychological and social mode of behavior that results from a charismatic leader and her followers sharing a mission and vision. Or at least a plan to do something their friends will think is cool. https://paulgraham.com/ace.html While founders do seem to have an advantage in achieving that mode of behavior, at least some professional managers seem to have achieved similar results in leading established companies by casting a vision and defining a mission that create win-wins through new products and services that make it easier for people to communicate. Perhaps "Founder Mode" is unique to what I am calling startup culture, but I don't see any reason why its most useful qualities might not be imitated by professional managers to social benefit. ↩︎